Photography, or at least this famous picture

Photography, or at least this famous picture  , has been crucial for the spread of Che Guevara’s image worldwide – and perhaps for the creation of his cult as well. But few people know that he was an avid photographer himself. In fact, he’s said that before becoming a comandante he was a photographer.

, has been crucial for the spread of Che Guevara’s image worldwide – and perhaps for the creation of his cult as well. But few people know that he was an avid photographer himself. In fact, he’s said that before becoming a comandante he was a photographer.

A pretty complete collection of his images was put together in 1990 by the Centro de Estudios de Che Guevara in Cuba. Since then, it has been presented as a traveling exhibition of over 200 photos in a dozen Latin American and European cities. I saw it laid out at the Museum of Rome in Trastevere (my favorite Roman neighborhood) last summer.

Little Ernesto’s interest in photography started with his father’s camera and then it was applied to the school newspaper he founded as a youth in Argentina. Later, while in Mexico following his motorcycle journey through Latin America, he got a contract with Agencia Latina (photographing the Pan-American Games of 1955, for which he was ultimately never paid) and also earned some of his living as an itinerant photographer in the parks and squares of Mexico City. He then continued taking pictures during the armed revolt in Cuba and through the course of the Cuban revolution; and even as he was traveling around the world as a member of the Cuban government. A very unusual experience as a photographer.

So, what is his photography all about, his approach, his technique, his interests? Although the accompanying video, produced by Havana’s Centro de Estudios de Che Guevara, praises his artistry, the images are more valuable for their subject matter and historic significance rather then for their artistic achievement. The themes are quite telling. There are some self portraits, presenting him working in a sea of papers or in a busy environment. He was quite conscious of the image he was building of himself and evidently worked on that. There are also family and friends pictures.

Another series is of Pre-Columbian monuments in Mexico. The indigenous substratum so important for his vision of Latin America, this attention to history is only logical. It is interesting to note, however, that he always included smaller human figures in those frames, as if to connect the legacy of the past to the fate of the descendants’ present. These images have their own independent power, especially compared to the rather tourist pictures he took during his travels around the world as part of Cuban governmental delegations in the early 60s. In general, his street work, especially in situations in which he could blend in the crowd, is often well executed and interesting. But then it’s impossible to be an inconspicuous witness with a camera when you are an official visitor of a foreign state.

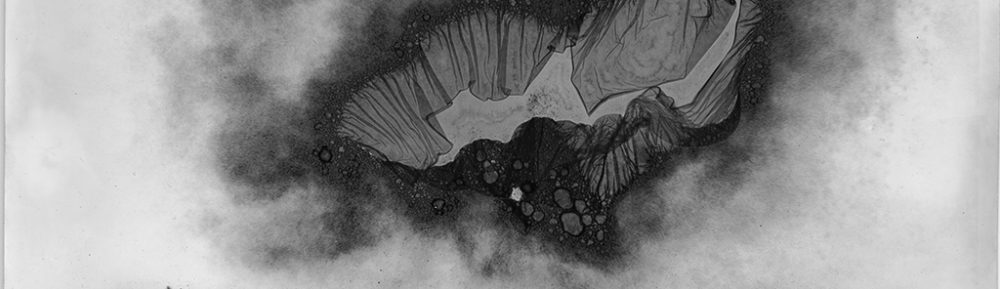

There are also, as it is to be expected, portraits of important figures, many of whom were his friends. There are abstract compositions, factory interiors and exteriors, scenes of mass events.

For those curious about his cameras, his preferred ones were Nikon S2 with a 50mm lens, Zenit 3M with a Helios 58/2 (it’s kept at his memorial museum in Santa Clara), as well as Plaubel Makina and Ihagee Exakta – and if I understood that correctly, a Leica 2 as well.

Are these photographs important to see? Are they exceptional or at least significant? Time certainly is an ally in increasing the value of an image, as we had the chance to see with Vivian Meier’s work, the late Chicago nanny whose negatives were recently discovered by accident. They didn’t show places or people much different from what we already knew life was in the 50s and 60s. They are not exceptional as art either; however, just the fact that we suddenly have access to images that were kept hidden for some time, of a bygone era, increased their appeal. So Che Guevara’s photographs certainly benefit from their time-lapse distance.

Still, I was left with so many questions at the end. What moved him to keep taking pictures even when it was difficult, cumbersome, redundant, not practically necessary? When his pictures wouldn’t make a big difference, when his point of view wouldn’t be original, like when he was on official trips? Why did he insist on being a witness with a camera while being an agent in the world as well?

It seems that some of the images were made to be seen by others; others were most probably for recording purposes for himself. They were like his text-based diary, laid out partially as a memory tool, as a way to process his experience or as a way of communication with others.

In the end, they are important also as a testimony for a historic person’s inner life. So this collection should be seen as his diary – beyond a testimony of what he saw and what happened to him, it is a document of how he viewed the world. It’s the google reader of his visual interests, which, it happens, were as important to him as his words and thoughts. It’s the mental visual itinerary of one of the most noted figures of the 20th century and for that it definitely gets its due attention.

Hi Ellie. I work for an online photography publication and I wonder if we can reprint your post on our website. Could you please contact me? Thanks!

Pingback: Zenit 3M: A 60s Soviet snapper « Zorki Photo

Pingback: Check grandma’s attic | The Mex Files

Pingback: Zenit 3M review – Zorki Photo